In the heyday of amusement parks, the phenomenon spread from the coasts and throughout the country. In many landlocked areas, however, the attractions they offered were experienced in an inverted form. Instead of traveling to visit a place of pleasures, the experience could come to you, through the long-standing tradition of the traveling carnival.

Just as amusement parks are often depicted as uniquely, desirably American, but also as potentially threatening places of misrule, we see conflicting ideas and mixed messages about traveling carnivals. The images of rides and funhouses, of young men winning prizes for their girls at games of chance, are enduring symbols of the American experience. Underneath, however, we can find ideas of threat, of sin, of outsiders bringing temptation to otherwise placid, close-knit communities, although sometimes it’s the other way around.

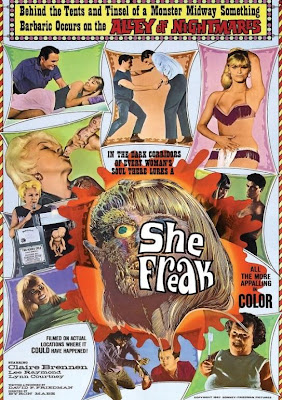

She Freak, written and produced by quintessential showman David F. Freidman and directed by Byron Mabe, borrows the outline of Tod Browning’s black and white classic, Freaks (1932), laying a version of its simple morality tale over the real-life West Coast Shows.

Part of the modern appeal of films like Night Tide and Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies is their documentation of real places, once major sites of American experience, that are now long-lost. This element is even more notable in She Freak, which provides an invaluable view of a vintage traveling carnival, not least in its delightful sideshow posters (for Alligator Girl, Monkey Girl, Atomic Girl, and Phantasma-Goria) and incredible wardrobe choices, like the snake handler’s psychedelic blouses and crochet vests.

As surf music instrumentals play over its colorful documentary footage of carny life—with long intervals of setting up tents, rides, and games, and longer intervals of tearing them down—it’s almost a shame that there has to be a plot at all.

According to the carnival blog Docs Midway Cookhouse, filming took place at the Bakersfield and Madeira, California Fairs; “Kern County,” where Bakersfield is located, is visible on some of the fairground buildings. The cooperation of West Coast Shows is thanked with a disclaimer, that the story “simply would not and could not happen in this time and setting,” now that the industry has been taken out of “the hands of mountebanks and gypsies.” This is amusing in light of the film’s sensational poster, full of advertising ballyhoo that echoes the carny patter in the film, which trumpets it as not only “all the more appalling in color,” but “filmed on the actual locations where it COULD have happened.”

She Freak is, like Night Tide, focused on the carnival people themselves, and presents a unique stage on which to critique the misuse of power. The character who’ll obviously become the villainous counterpart to Freaks’ Cleopatra has a plausible, understandable motivation. Potentially sympathetic at the start, she is hardened by experience, so that when she gains a position of power, she is greedy and unfeeling, becoming part of the system that made life hard for people like her, instead of having solidarity with them.

The film opens with that carnival set-up, and the barker who reminds us that “there are only two kinds of freaks, ladies and gentlemen. Those created by God, and those made by man.” From there, we shift to a small-town diner, where above-it-all waitress Jade scorns the advances of the customers. “You sure don’t give those rednecks the time of day, do you?” her lecherous boss asks, and the answer is a definite “no.”

Jade starts out pretty tough-talking, and isn’t entirely sympathetic, but she makes valid points about her dead-end life and the example of her unhappy parents. “I know who I am. I’m nobody, just like you … There’s gotta be something better than that. I don’t know what or where it is, but when I find it, I’m gonna get it. Even if I have to lie or beg or cheat or steal for it, I’m gonna get it.” When the carnival’s marketer tries to talk her out of applying for a job, saying “it’s a rugged life,” she merely replies, “what ain’t?”

Thank goodness the Internet exists to explain this hand-written sign in the diner: “YCHJCY A ¼ FTJB.” It’s a gag with the answer, “Your curiosity has just cost you a quarter for the juke box.”

There’s a seductively nostalgic quality to She Freak; the specificity of the time period shows up in the clothes, the room decors, and the soundtrack, creating a vivid sense of a very particular bygone day. But the story includes the fact that the “good old days” were a time when a small-town bully could feel free to harass an employee, then fire her at will for rejecting his advances. A young woman like Jade had few real career prospects, and even when she joins the carnival, her opportunities don’t expand that quickly: in a surprisingly realistic touch, she ends up at the Midway Diner, doing the same job she was already doing.

She makes a friend, attractive “Moon” Mullins, who’s pleasant and welcoming, and Jade isn’t at all judgmental about her position as a stripper in the Paris at Midnite show (advertised as “50 million Frenchmen can’t B wrong: Ooh! La! La!”). Everyone needs to make a living, and everyone else is matter of fact about the reality. But the new girl doesn’t want to listen to the old pro’s advice about steering clear of the flirtatious Ferris wheel operator, and she isn’t so tolerant about the freak show, even though all we see is the sword swallower and that stylish, motherly snake handler.

Their conversation at this point more or less gives us the film’s mission statement.

Moon: The freaks? So?

Jade: They’re so horrible.

Moon: Honey, God made ‘em the way they are. They’re better off around here than most places.

Jade: Why do they have to be anywhere?

Jade’s desire to better herself is warped into a sense of contempt for those she perceives as abnormal and in some way lower than herself. Once she indulges that intolerance, she begins to turn in a different direction. Before long, she’s pumping Moon for information about which men have enough money to be worth pursuing. The best prospect is Steve, who runs the freak show. He’s a decent guy, who treats the freaks with respect and considers them friends, with whom he’s in a cooperative business, so when Jade continues to call them “disgusting,” that should be a real red flag.

Despite these improved prospects, she still takes up with trouble-maker Blackie on the side, and given the insular nature of the small community, she’s clearly not thinking this through. She and her future husband even have a romantic ride on Blackie’s Ferris wheel, which is asking for trouble.

By the time Jade marries her sugar daddy, Moon subtly disapproves of her friend’s transformation into a hardened gold-digger. At one point, one of the carnies refers to Jade as a “hash-slinging yokel,” but the boss defends her as “just a little country gal looking for something better,” reminding us of her original motives. Joining the carnival, going out on the road to make one’s fortune, is treated as a kind of contemporary American version of the frontier. There was nothing wrong with Jade’s ambitions, and her desire for more opportunities and new experiences was perfectly understandable. But once she starts down the path, her goals become a moving target. She isn’t satisfied with what she gets, but keeps wanting more, and one moral compromise quickly leads to another.

Broadly speaking, there are two general responses to struggle and hardship: either becoming more compassionate to the struggles of others, or more hard-hearted. Here, the apparent protagonist becomes the villain. Her aversion to those who are different from her, lower and suffering more than she did, and her inability, or unwillingness, to overcome it, are the first steps in indulging her negative side, to the detriment of the better instincts she showed earlier on.

Attaining wealth and freedom, she is corrupted by power, leading to a violent, Browning-inspired comeuppance. The message of the film could be interpreted as a condemnation of the small town girl’s independence and ambition: that she should, perhaps, stayed in her place and not reached out for more. Fortunately, the character of Moon helps balance this idea. Her job as a stripper doesn’t impair her dignity or her moral compass, just as the freaks have their own dignity and sense of community, outside the mainstream of society. Jade, though, destroys her ties of friendship and connection with others, choosing to become the worst kind of boss and the worst kind of rich person, looking down at anyone she sees as lower than herself, which was never necessary or inevitable.

Early on, Moon had told her, “you’re with us, you belong.” Jade took advantage of the carnival’s countercultural opportunities to escape the stifling limitations of normal, everyday life, but she didn’t respect them, or the people who were happy to include her in their community and even their family. Obviously, no one’s condoning what happens to her, which is disproportionate to her sins, but this is clearly not a realistic twist, but more of a fable, in which nothing bad would have happened if people had done the right thing.

While there isn’t a whole lot of story, the film looks surprisingly good, considering the speed and budget of the production.

Lead actress Claire Brennan had a long career, mostly in 1970s TV, but the most famous name in the cast is 3’11” actor Felix Silla, who appears here as cowboy Shorty, and would play Cousin Itt on The Addams Family. Internet rumors claim the two started a long-time secret relationship during shooting, eventually having a child, but this is difficult to confirm.

The website Sideshow World, packed with behind-the-scenes information about life on the sideshow circuit, includes memoirs by magician Vanteen, who played Mr. Babcock, the man who gives Jade her job at the carnival, and he describes the filming of She Freak at some length. He and the snake handler (billed as “Madame Lee”) were married in real life, and the film depicts her own real-life snake act, so the feeling of documentary, less often found in later genre films, is well-earned.