As colleges welcome their students back for the new school year, and don’t get me started on real-world issues, we’re featuring a few campus-set horror movies that deserve more love.

Director Jack Arnold’s is revered for his work on the all-time classic Universal monster movie The Creature from the Black Lagoon and its sequel, Revenge of the Creature. He also directed famous genre films like It Came from Outer Space, This Island Earth, Tarantula, and The Incredible Shrinking Man, not to mention one of the equally all-time classic MST3K shorts, “The Chicken of Tomorrow” (“in a deadly battle against the Chicken of Today.") Later in his career, he primarily directed for TV. His last credit, in 1984, is for his 8th episode of The Love Boat, one in which teenage Vicki gets drunk and Captain Stubing has a heart-to-heart with her about his alcoholism. Quintessential!

He also directed an episode of The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries called “Campus Terror,” which was the tagline on the poster for our first Back to School Special, 1958’s Monster on the Campus, a film that has received significantly less attention than many of his other works, but which totally agrees: We Are Devo.

Unlike so many later horror films, the focus here is on adults, not on the students. The college setting would seem ideal for young audiences, who were flocking to the new science fiction and horror films, to relate to, but this one doesn’t offer them much in the way of audience identification. The academic environment is more important thematically, as a forum to explore evolution and its counterpart, devolution. The campus, a site of education, progress, and general intellectual advancement, can be potentially threatening as well as enlightening. Study can lead, indirectly, expose people to something dangerous, and here those dangers are extrapolated to outright physical ones.

This idea is reinforced by Dr. Blake’s speechifying and his general attitude toward life. His fiancée Madeline argues that “Humanity still has a future,” but the professor is dour about its chances, believing that unless it can learn to control its primitive instincts, “the race is doomed.”

This idea is reinforced by Dr. Blake’s speechifying and his general attitude toward life. His fiancée Madeline argues that “Humanity still has a future,” but the professor is dour about its chances, believing that unless it can learn to control its primitive instincts, “the race is doomed.” More on this theme: “Man can use his knowledge to destroy all spiritual values and reduce the race to bestiality. Or he can use his knowledge to increase his understanding to a point far beyond anything now imaginable.” Also, “Man’s only one generation from savagery” and “Civilization isn’t inherited, it’s learned.” And “The past is still with us … It’s the savage in modern man that science must meet and defeat if humanity is to survive.” He’s pretty gloomy for a guy with a good job and an attractive, supportive fiancée well-placed to help his career.

Some scholars, like Patrick Gonder, see a message about segregation and integration in the film, that the devolved throwback represents a white supremacist fear of black Americans, often coded at the time in the language of the primitive. This is certainly a possibility, and an interesting angle. It’s clear that white men at the time believed they had things to fear from black advancement, even as they continued in their positions of power. Gonder's excellent essay is online here, so check it out.

Dr. Blake is deeply worried about the survival of humanity’s baser instincts, pontificating about this at length, but it’s his experimentation, his efforts to understand the primitive state in order to rise above it, that unleashes these forces. Without his fear of devolution, this extreme form of devolution wouldn’t have happened, and a lot of people would still be alive. This seems to reflect a popular distrust of science and what it might lead to, especially with something like evolution. The Scopes trial took place decades earlier, well before any college students of 1958 were born, but anxieties about evolution and its teaching have never left American life.

The students’ perspective on all this is largely unexamined, but when Blake dismisses class to work on the fish, the students are mostly happy about it, some of them going off to a movie instead. In the background, though, you can hear one of them complain, “Don’t you want to get an education?” Academia is maybe most strongly represented by Madeline’s father, an administrator hoping that the prehistoric fish will bring in publicity and alumni donations. He says, “An institution’s like a living organism. The moment it stops growing, it starts degenerating. So, anything that promotes growth is all to the good.” So the language of science, even of evolution and devolution, is put in the service of capitalism. Later, even after mysterious deaths start happening on campus, his real tipping point is when Dr. Blake makes a lengthy and expensive phone call to Madagascar, at “$5 a minute!” which is unusually realistic.

I have to note that Dr. Blake goes to a cabin in the woods to record his story on an old-school tape recorder, which is very Evil Dead.

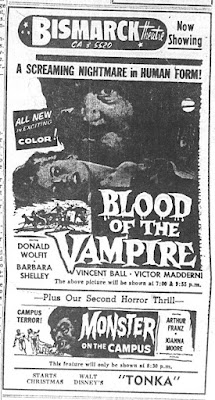

It’s all over the Internet that this movie premiered December 17, 1958, in Bismarck, North Dakota, a real WTF? I could not find a citation, and the same sentence with this factoid is repeated in tons of places, so I couldn’t track down the original source. It did play there at the Bismarck Theatre in December 1958, as a double feature with The Blood of the Vampire, which was originall released in October 1958. After Interlibrary loaning microfilm reels of the Bismarck newspaper and scrolling through them, though, I feel fairly certain of one thing: if Monster on the Campus did indeed premier in Bismarck, nobody in Bismarck knew that at the time.

It's only mentioned in the regular columns about the films currently playing in town, and even there, only in passing, barely footnotes to material about bigger pictures like the thriller Cry Terror! and Disney's Tonka. The Bismarck Tribune stated on 12/12/58 that "Wednesday through Saturday a double feature shocker will show at the Bismarck. Blood of the Vampire is one half of the feature, Monster on the Campus the other ... Both movies have their crazed monster created in the medical laboratory." They were mentioned again on 12/19/58: "A dim-witted, one-eyed hunchback ... runs wild in Blood of the Vampire. In Monster on the Campus, a test tube horror takes its toll. Of course pretty girls have to be the victims in each show."

I did not cross-reference with our own library's microfilm to see if Monster on the Campus played any local theaters at the same time, or any other cities, because I was already microfilmed out. All I can say is that the Bismarck showing has no indication that it's a premiere, or that it's anything but part of a regular B-movie package. Of course, who know? As Dr. Blake says, rather metafictionally about the plot of his movie, it's "as improbable as life itself!"